.webp)

© History Oasis

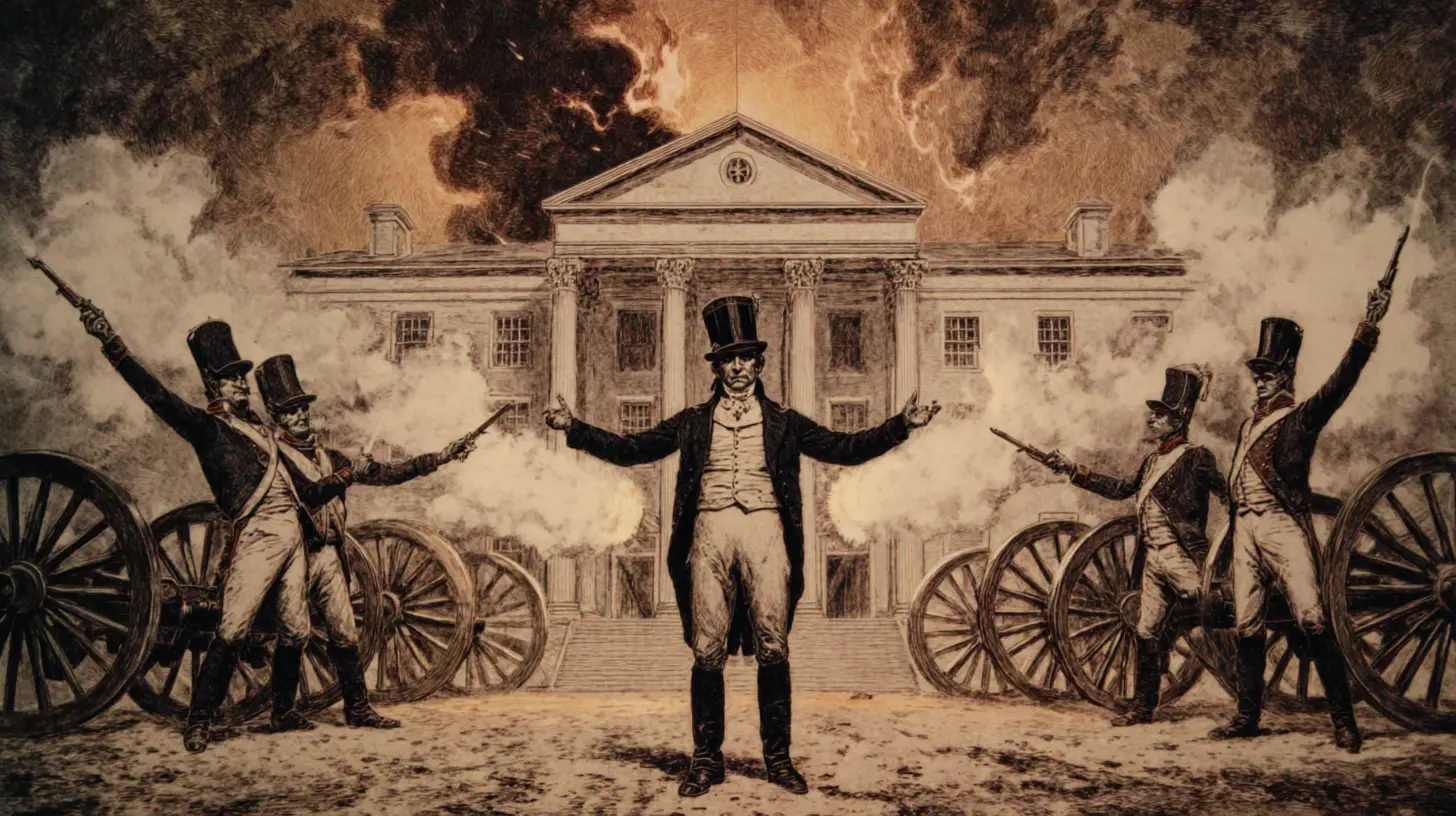

On August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, British troops marched into Washington D.C., ate the president's abandoned dinner, and burned the capital to the ground in just 26 hours.

These are the crazy events that followed.

British troops stormed the White House on August 24, 1814, and found dinner still warm on the table. President James Madison had fled so fast he left behind a complete feast. The British officers sat down and ate Madison's meal, drank his wine, then burned the house to the ground. Captain Blanshard later reported they enjoyed the food while the building still stood. Adding insult to injury doesn't quite cover it.

Everyone gets this fact wrong. Dolley Madison didn't personally rescue the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington. The painting hung too high—she'd have needed a ladder. And the British were blocks away. What Dolley actually did was organize the evacuation. She grabbed silver, gave orders, kept her head while chaos closed in. The two people who saved the painting were Jean Pierre Sioussat (the French doorkeeper) and McGraw, the president's gardener. They cut the canvas from its frame and loaded it onto a wagon. By the time the British arrived, Dolley was gone and the painting was safe. She deserves credit for leadership under pressure. But the physical act of saving that painting? Two other people did that work.

Less than four days after the British set Washington ablaze, a massive storm tore through the capital. Possibly a hurricane. Definitely a tornado. It touched down on Constitution Avenue, picked up two British cannons, carried them through the air, and dropped them yards away. It killed British soldiers and American civilians. The winds were so violent the British troops left faster than planned. Some historians say the storm caused more damage than the British did.

The British didn't just use torches. They piled furniture, doused it with gunpowder paste, and created makeshift bombs inside the Capitol and White House. They wanted these buildings to burn from the inside out. The flames in the Capitol's southern wing grew so hot the British couldn't gather enough wood to burn the stone walls completely. The heat melted glass skylights into puddles on the floor.

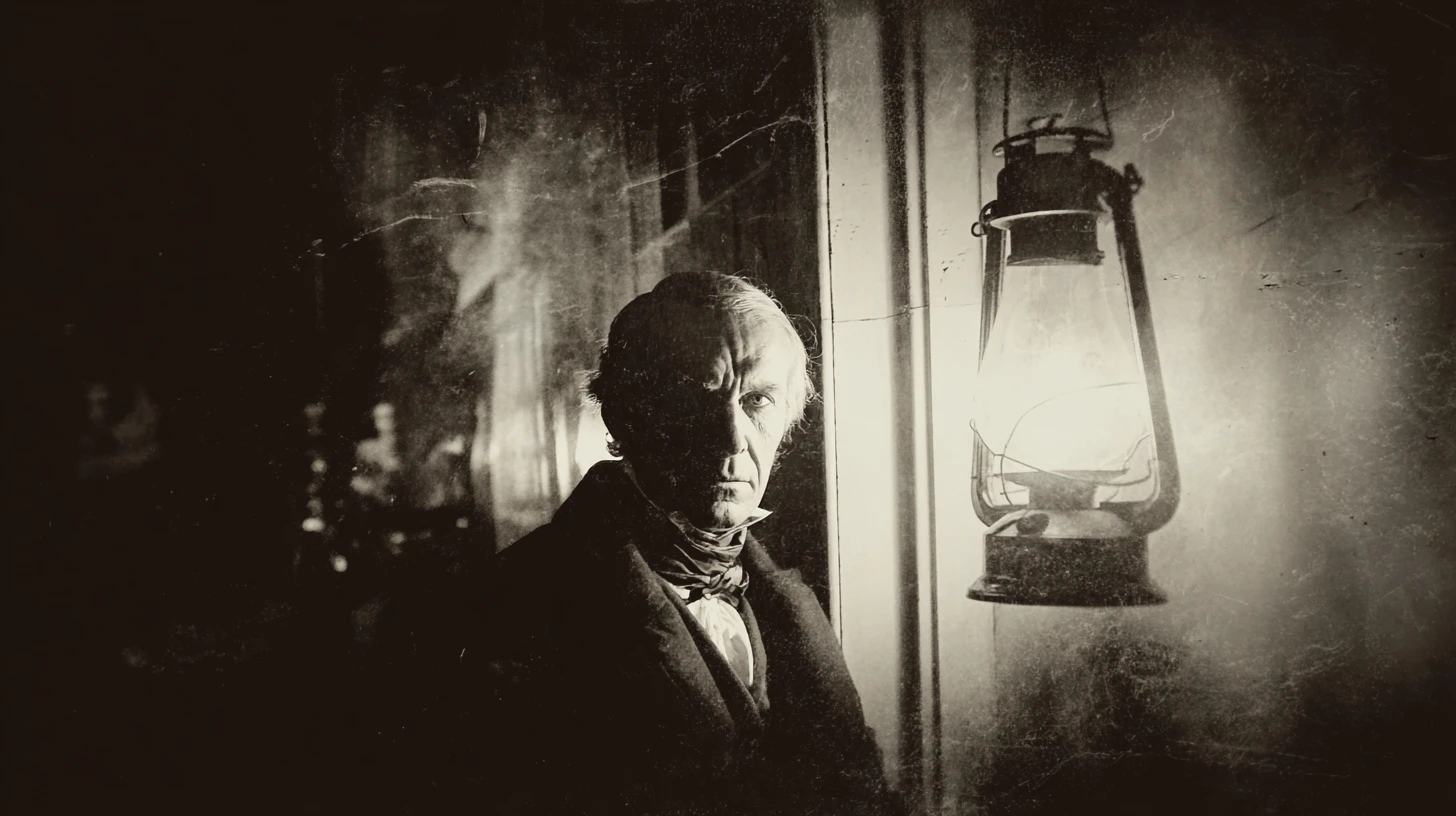

Paul Jennings was James Madison's enslaved attendant. He was fifteen when he watched the British invasion. He later wrote the first memoir ever published by a White House staff member. Jennings corrected the myth about Dolley and the painting, explaining exactly who saved it and how. He described preparing dinner for the president's party, only to watch British soldiers eat it. After buying his freedom, Jennings published his account in 1865. In 2009, President Obama held a ceremony honoring Jennings. A dozen of his descendants visited the White House to see the painting their ancestor helped save.

William Thornton stood in front of British soldiers with a loaded cannon aimed at the Patent Office. He threw himself in front of the gun and shouted: "Are you Englishmen or only Goths and Vandals? This is the Patent Office, a depository of the ingenuity of the American nation, in which the whole civilized world is interested. Would you destroy it? If so, fire away, and let the charge pass through my body." The soldiers lowered their weapons. The Patent Office was the only government building left standing.

Rear Admiral George Cockburn walked into the National Intelligencer newspaper office planning to burn it down. The paper had called him a "Ruffian." But local women convinced him not to—the fire would spread to their homes. So Cockburn ordered his troops to demolish the building brick by brick. Then he told them to destroy all the letter "C" type pieces in the printing press "so that the rascals can have no further means of abusing my name." Petty doesn't begin to cover it.

On August 25, British troops found 150 barrels of gunpowder the Americans left at Fort McNair. While trying to dump the powder into a well, it ignited. The explosion killed as many as thirty British soldiers and injured many more. The Royal Navy's official casualty report for the entire Washington campaign listed one man killed and six wounded in combat. The fort explosion caused far more British deaths than any American resistance.

The British were retaliating. American forces had burned York (now Toronto) in 1813 and torched Port Dover in 1814, destroying homes and private property. Sir George Prévost, Governor General of British North America, called for payback against American "wanton destruction" in Canada. British commanders had orders to spare civilian lives but destroy government buildings. Major General Ross refused to burn the entire city, despite Admiral Cockburn's push to do so. They targeted symbols of American power, not homes.

The British entered Washington on the evening of August 24 and left by the evening of August 25. Twenty-six hours. They never intended to hold the city. Their orders were clear: raid, destroy government buildings, leave. This was a hit-and-run operation designed to humiliate the United States and draw military resources away from Canada.

After the burning, Congress had nowhere to meet. They gathered at the Post and Patent Office building inside Blodgett's Hotel, one of the few structures large enough to hold all members. They met there from September 19, 1814, until December 1815, when the Old Brick Capitol was finished. The Capitol building itself took twelve years to reconstruct. The Old Brick Capitol cost $25,000 and took five months. The actual Capitol? Twelve years and far more money.

When British forces left Washington, they took two pairs of portraits of King George III and Queen Charlotte back to Bermuda. One pair hangs in the House of Assembly of the Parliament of Bermuda. The other is in the Cabinet Building. Both are still there in Hamilton. The British found them in a public building and figured they belonged in British hands.

The Capitol housed the Library of Congress in 1814. When the British set fire to the building, they destroyed the entire 3,000-volume collection. The flames consumed books, decorations, sculptures, columns, and pediments. Wooden ceilings and floors burned completely. Glass skylights melted. The superintendent calculated the total damage to the Capitol at $787,163.28 (about $11.8 million today). Thomas Jefferson later sold his personal library to the government to rebuild the collection.

While Washington burned, President Madison evacuated to Brookeville, Maryland, a tiny town in Montgomery County. He spent the night at the house of Caleb Bentley, a Quaker silversmith. The town is now known as the "United States Capital for a Day." Bentley's house still stands. You can visit it today.

Major General Robert Ross, who led the 4,500-man British army, was skeptical from the start. Historian John McCavitt notes that Ross "never dreamt for one minute that an army of 3,500 men with 1,000 marines reinforcement, with no cavalry, hardly any artillery, could march 50 miles inland and capture an enemy capital." Ross planned for an orderly surrender. He wanted to damage only public buildings. When his troops entered under a flag of truce, remaining American forces opened fire, killing two of his men and wounding his horse. That's when Ross reluctantly ordered the burning. He was described as "an officer and a gentleman" who never wanted things to escalate the way they did.