.webp)

Ferrero Group

Most candy bars aim for simple pleasure. The 100 Grand Bar reached for something else: the fantasy of instant wealth. Launched in 1964 when game shows promised fortunes to everyday Americans, this Nestlé creation turned that dream into something you could hold, unwrap, and eat for pocket change.

The name was the hook. Everything else was chocolate, caramel, and crisped rice.

Here’s how a game show gimmick became a candy aisle staple.

In 1964, Nestlé faced a crowded market. Hershey’s dominated. Mars kept innovating. Breaking through the noise required more than another chocolate bar.

Shows like “The $64,000 Question” and “The Big Surprise” had Americans dreaming of winning big. The format was simple: answer questions, win cash, change your life. Millions watched. Everyone fantasized.

Nestlé asked: What if we bottled that feeling?

The “$100,000 Bar” launched with a promise its competitors couldn’t match. Not better taste or more chocolate. Just a name that made you imagine winning. You couldn’t actually win $100,000. But for a few cents, you could pretend.

The formula itself was straightforward. Milk chocolate coating. Chewy caramel center. Crisped rice for texture. Nothing new. The genius lived in the wrapper and marketing.

The first commercials for $100,000 leaned into the theater. Four men in striped gangster suits and fedoras sang in tight barbershop harmony: “Why don’tcha do yourself a favor... And get a hundred grand in flavor!”

“Tastes so good it’s almost illegal!” became the candy’s slogan.

Nestlé positioned the candy as contraband, something illicit and desirable. The gangster aesthetic played on 1930s nostalgia while winking at consumers. You’re not just eating candy. You’re getting away with something.

The approach worked. The bar gained recognition fast. The name stuck in people’s heads. Radio jingles repeated it. Kids asked for it by name.

Ten years in, Nestlé scrapped everything visual. The original packaging was functional but forgettable.

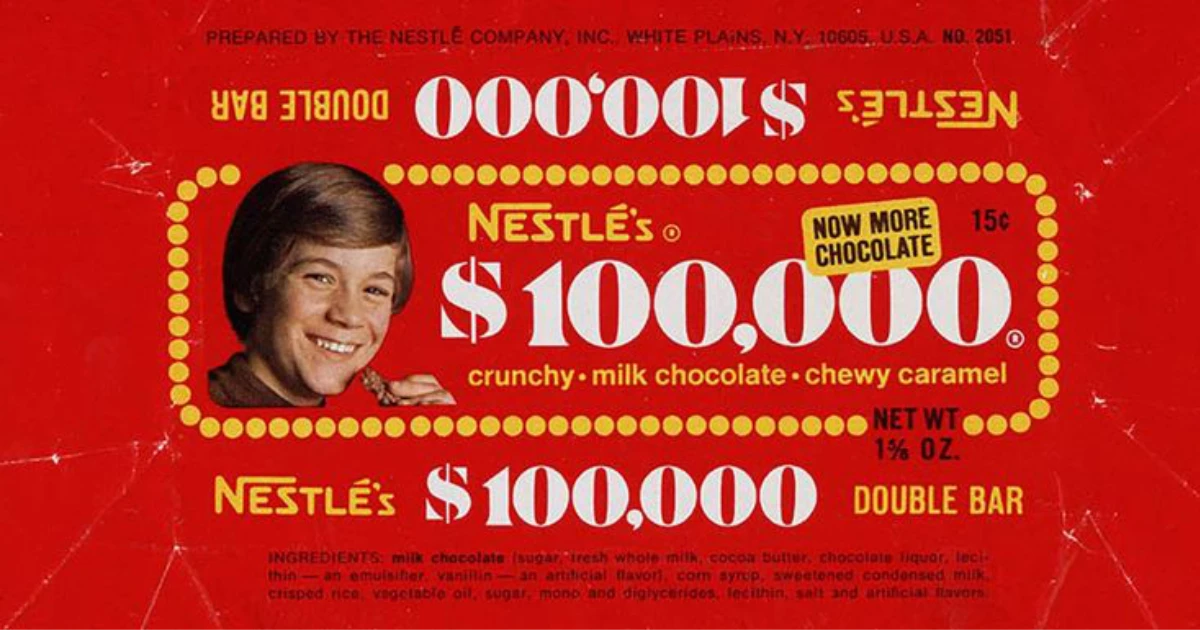

The 1973 redesign changed the game. Bright colors replaced muted tones. And they designed a smiling kid clutching the candy bar, radiating pure joy.

This “kid wrapper” era defined the brand for decades. The image communicated instantly. This candy makes children happy. This candy is fun. This candy is yours.

The psychology of the campaign was smart. Adults might roll their eyes at a candy bar named after money. Kids didn’t care about the joke. They saw another kid smiling and wanted in.

The redesign also signaled staying power. Nestlé was investing, not maintaining. The $100,000 Grand Bar wasn’t a novelty. It was a brand.

Twenty years after launch, Nestlé made a structural change. The single large bar split into two smaller pieces.

The official reasoning: consumer preference and sharing convenience. Two pieces meant more surface area for chocolate coating. It meant splitting with a friend. It meant eating one now, saving one for later.

The real truth was that smaller pieces felt like more. The same amount of candy, repackaged, seemed generous.

This move also matched competitors. Most candy bars came in bite-sized or split formats. The candy bar was adapting while maintaining its identity.

Trademark law forced Nestlé’s hand. “$100,000 Bar” was too generic. Courts wouldn’t protect it. Other companies could use similar names. The brand was vulnerable.

The solution: drop the dollar sign and zeros. “$100,000 Bar” became “100 Grand.”

Shorter. Cleaner. Legally defensible.

The meaning stayed intact. Everyone understood what “100 Grand” meant. The fantasy remained. Only the packaging changed.

Fans barely noticed. New customers learned the shorter name. The bar kept selling.

The name change couldn’t prevent what came next. Radio DJs discovered comedy gold.

The setup was perfect: announce a contest. Promise listeners “100 Grand” if they call in and win. Wait for calls to flood in. Award the winner a candy bar.

Stations across America ran versions of this prank. Some listeners laughed. Many got angry. A few threatened legal action.

Nestlé couldn’t stop it. The name was public. The joke wrote itself. Free publicity flooded in, even if some came from frustrated contestants.

The pranks revealed something interesting. The 100 Grand Bar had achieved cultural penetration. People knew it well enough to feel tricked. The candy had become a reference point and… a punchline.

“The Office” featured Michael Scott using 100 Grand bars as employee motivation. Stephen Colbert worked them into comedy segments. The candy bar kept appearing in pop culture.

This wasn’t product placement. Writers reached for the 100 Grand because audiences would get the joke instantly. The name carried humor. No explanation needed.

Six decades after launch, the original marketing concept still landed. A candy bar named after money was funny. Simple. Repeatable. Timeless.

In 2018, Nestlé shifted focus toward health foods. The candy division no longer fits the company’s strategy. Ferrero Group, the Italian confectionery giant, saw an opportunity.

The deal: $2.8 billion for Nestlé’s entire U.S. candy business. Butterfinger, Baby Ruth, Crunch, and others moved toFerrero. The 100 Grand went with them.

Ferrero promised to maintain recipes and heritage. The Italian company knew American candy culture. They owned Nutella and Ferrero Rocher. They understood treats.

For the 100 Grand, ownership changed, but the product didn’t. Same formula. Same wrapper design. Same spot on store shelves.

Walk into any store today. The 100 Grand sits there, unchanged. No website of its own. No spin-off flavors. No limited editions or seasonal variations.