.webp)

Smarties

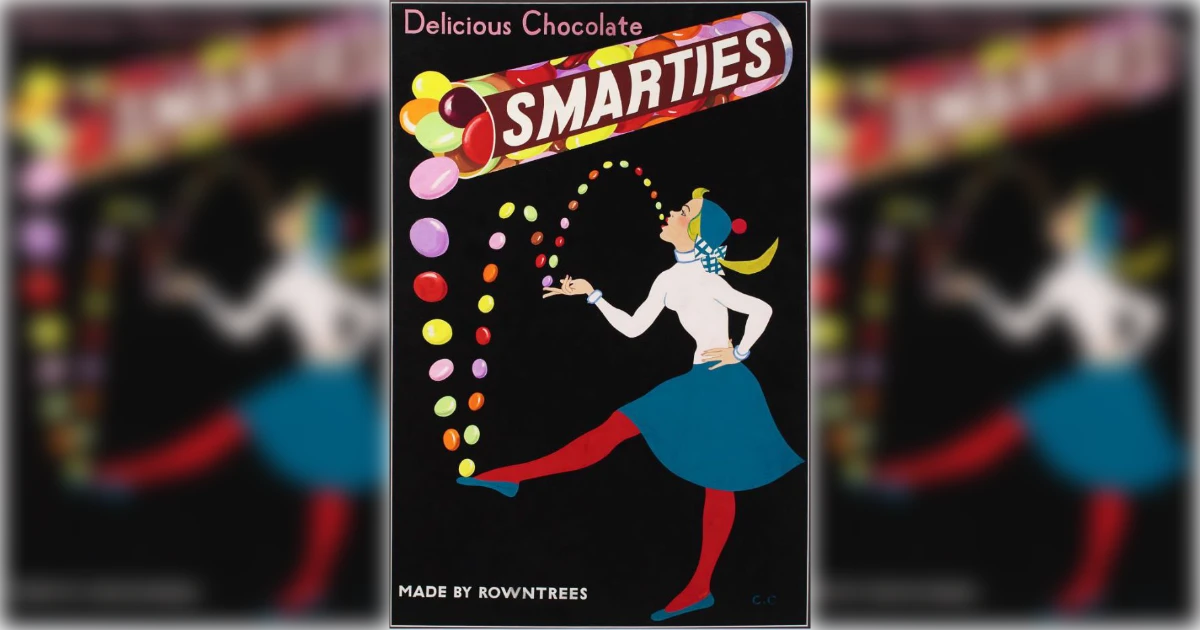

In 1882, Rowntree's factory in York made something called Chocolate Beans. Small chocolate pieces with sugar shells. Nothing special. Nobody really cared.

Fifty-five years passed.

George Harris returned from America in 1937 with fresh eyes. He had watched American companies transform ordinary products into brands with personality. He looked at those forgotten Chocolate Beans and saw possibilities.

He renamed them Smarties.

The effect was instant. By 1938, Rowntree built a new factory block just for Smarties. Months later, they expanded it. The simple name change had unleashed something unexpected.

July 1942. Chocolate went on ration. Rowntree faced a choice: make inferior Smarties or make none at all.

They chose none.

For four years, British children went without. When Smarties returned in 1946, even made with plain chocolate instead of milk, people lined up. Quality had mattered more than quick profits.

By the 1950s, their first TV ad declared Smarties the "sweetest, treatest, best to eatest." The awkward rhyme worked.

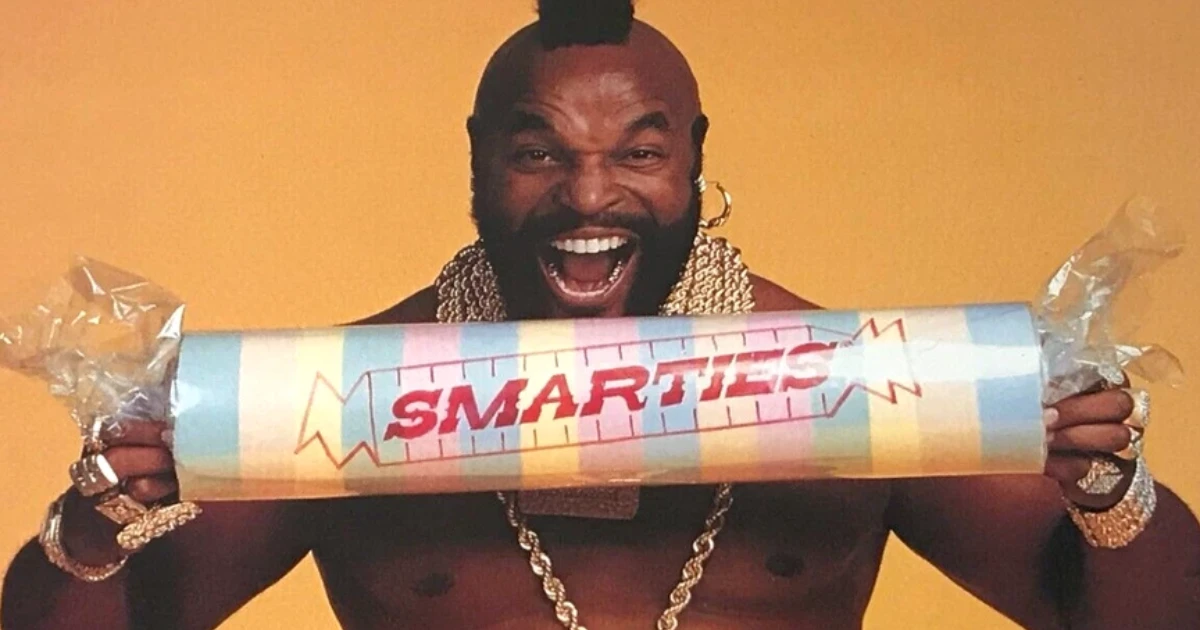

In 1949, Edward Dee stepped off the boat with his family. He brought two machines and a plan. The machines had made gunpowder pellets during World War II. Dee figured they could make candy tablets instead.

He rented space in Bloomfield, New Jersey. The machines compressed sugar into small, chalky discs. He called them Smarties, unaware that an ocean away, another company used the same name for chocolate.

American kids liked the tablets. Simple. Sweet. Cheap. By 1963, Dee needed a Canadian factory to meet demand.

There was one big problem. Nestlé owned the "Smarties" name in Canada.

So he called them Rockets there. Same candy, different name.

Nestlé took over Rowntree in 1988. Workers worried. Managers protested.

Rowntree fought back with color. They introduced blue Smarties as a limited edition, part of a campaign against the takeover. They made "I Support Blue Smarties" badges.

The blue Smartie became wildly popular. What started as a protest became a permanent solution.

In 2006, Nestlé committed to removing artificial colors. Seven colors transitioned easily to natural dyes. Blue had no natural source.

They removed blue Smarties. Replaced them with white.

Customers revolted. For two years, Nestlé scientists searched. Finally, they found spirulina seaweed produced the right blue.

February 2008. Blue returned. Britain celebrated.

%20.webp)

Today, the division is clean.

Europe, Canada, Australia: Nestlé's chocolate Smarties sell 50 million tubes yearly in Britain alone. Production moved from York to Hamburg in 2007, but the product stayed the same.

In America, the Dee family's third generation runs Smarties Candy Company. Two factories produce 2.5 billion rolls yearly. Halloween would feel incomplete without them.

Each company owns "Smarties" in their territory. No conflict. No confusion. Just two successful candies sharing a name across an ocean.

The British version survived wars, corporate takeovers, and ingredient controversies. It pioneered natural food coloring and showed heritage brands could evolve.

The American version proved immigrants could build lasting businesses. Edward Dee's granddaughters still run the company he founded in a rented room.