.webp)

Mary Jane

In 1884, Charles H. Miller set up a candy operation in a Boston house with an unusual pedigree. Paul Revere had lived there a century earlier, launching his midnight ride from that same address at 19 North Square.

Miller had no grand vision. He just made candy in the kitchen with his sons, experimenting with molasses recipes like dozens of other Boston confectioners. The city's port brought in cheap molasses, and the candy makers knew how to use it.

For three decades, the Miller family tested formulas. Then, in 1914, Charles N. Miller, the founder's son, mixed peanut butter into molasses taffy. The combination worked. The peanut butter softened the molasses, creating something new.

He called it Mary Jane.

The company claimed he named it after his favorite aunt. Others suspected he borrowed from a popular comic strip character for free publicity. When the comic's creator sued for copyright infringement, Miller won. The name stuck.

The candy came wrapped in yellow wax paper with a red stripe. A cartoon girl in a bonnet decorated each piece. The price: one penny. The slogan was direct: "Use your change for Mary Janes."

What saved Mary Jane was stubborn resistance to change. While other candy makers adjusted recipes to cut costs, the Miller company kept everything identical. Same formula. Same wrapper. Same mascot.

This wasn't sentiment. It was smart business. Customers knew exactly what they were getting. Year after year, decade after decade, Mary Jane tasted the same.

The candy survived the Great Depression. It survived two world wars. It became background music in American life, always there, never changing.

In 1989, after 75 years, the family sold the business to Stark Candy in Wisconsin. Production left New England for the first time.

The story was in for a twist in 2008.

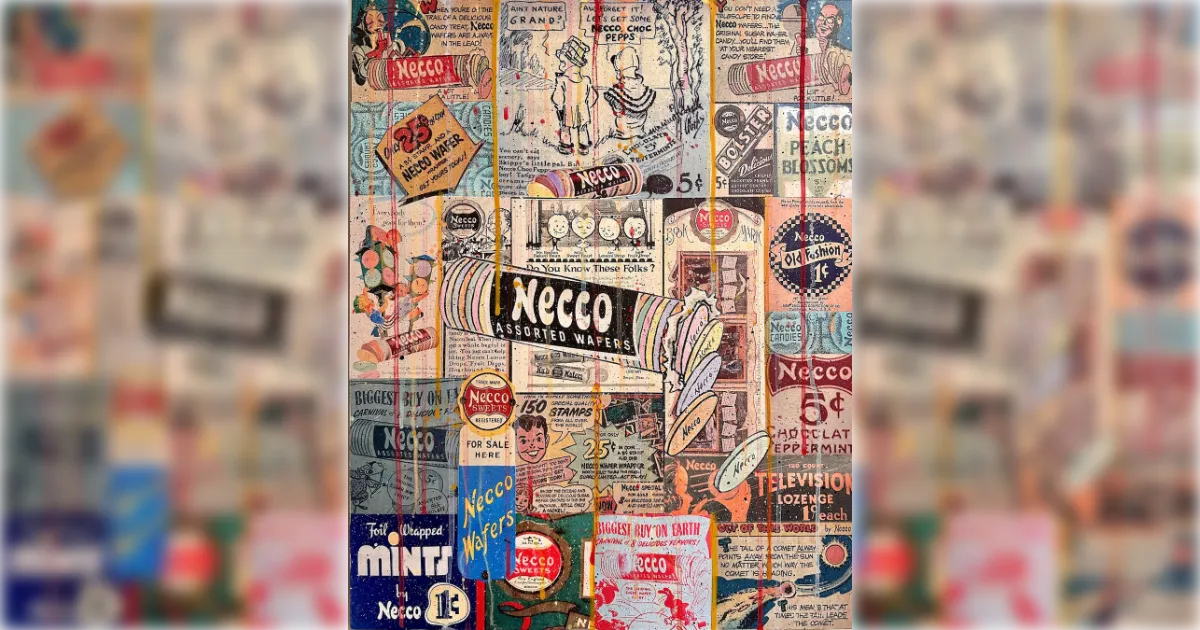

NECCO, the New England Confectionery Company, bought Stark and brought Mary Jane back to Massachusetts. The candy that started in Boston returned home after a 19-year detour.

NECCO had operated near Boston since 1847. They made Necco Wafers, Sweethearts, and Sky Bars. Adding Mary Jane to their lineup made sense. Everything seemed stable.

Then 2018 arrived.

FDA inspectors found rodents in NECCO's factory. Not for the first time—this was the fifth citation. Financial trouble mounted. In March, the company warned of massive layoffs. Customers panicked and bought whatever stock remained.

By May, NECCO declared bankruptcy. Spangler Candy bought the assets at auction for $18.83 million. They wanted Necco Wafers and Sweethearts. They took Mary Jane because it came with the package, but had no plans to make it.

Mary Jane sat dormant. Stores sold their remaining stock. Then the shelves went empty.

For two years, Mary Jane candy was discontinued. After 104 years of continuous production, the candy that survived everything finally stopped.

Atkinson Candy in Lufkin, Texas, made nostalgic treats: Chick-O-Stick, Slo Poke, and Black Cow. They understood old-fashioned candy.

In 2019, Atkinson negotiated a licensing deal with Spangler. They would make Mary Jane again, but with updates. The sticky yellow wax paper had frustrated customers for decades. Atkinson replaced it with twist wraps. They made the pieces smaller and easier to eat.

The formula stayed unchanged. Peanut butter and molasses, mixed the same way Charles N. Miller had figured out in 1914.

Production resumed in 2020.