.webp)

© History Oasis

The oddest fashion trends that are no more.

R.C. Milliet patented the cage crinoline in Paris in April 1856. Women wore these steel-hooped frameworks under their skirts. The structures reached six yards around at their widest point. By 1868, the smaller crinolette took over. By 1878, crinolines were gone. Why did they go out of fashion? One word. Fire. Florence Nightingale counted at least 630 deaths from crinoline fires in 1863-64 alone. Total deaths reached around 3,000.

Amelia Bloomer promoted this outfit through her newspaper, The Lily, in April 1851. Women wore knee-length dresses over Turkish-style trousers that gathered at the ankle. The Lily's circulation jumped from 500 to 4,000 after Bloomer announced she'd adopted the style. Men called women who wore them "Amazons" or "male impersonators." In October 1851, police arrested three women in bloomers after they drank too much at a London saloon. The ridicule was so fierce that women dropped the style within a year.

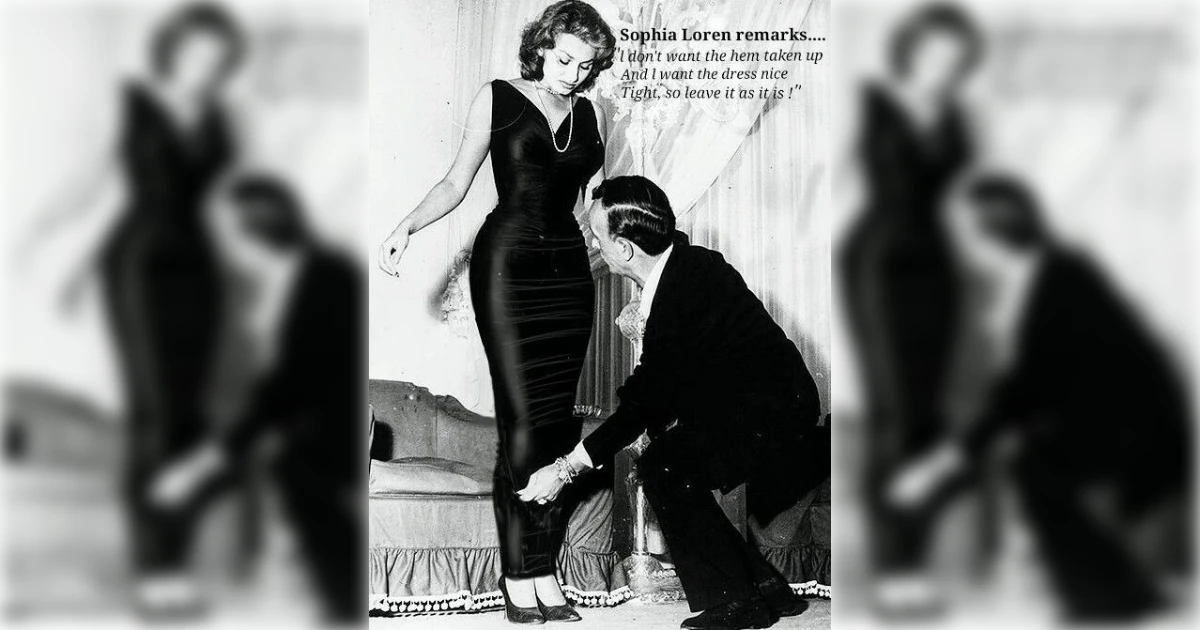

Paul Poiret created this restrictive fashion around 1908. The ankle-length skirt had a hem so narrow that women could barely walk. The design may have come from Mrs. Edith Ogilby Berg, who tied a rope around her skirt at the ankles during a 1908 Wright Brothers airplane demonstration. The skirts killed several people, including a woman trampled by a loose horse at a Paris racetrack in 1910. In 1912, the New York Street Railway added special cars with no steps to help women board. Illinois and Texas both considered banning them in 1911.

Discontinued: Late 1950s

Juli Lynne Charlot made the first poodle skirt in 1947 because she needed a Christmas party outfit, but had no money and couldn't sew. She only had felt from her mother's factory. Charlot started with Christmas themes, then made a dachshund design before the poodle version in 1948. The wide swing felt skirts with appliquéd designs became a teenage staple from 1950 to 1955. By 1952, mail-order catalogs sold only poodle skirts. Designer Bettie Moorie even made versions with playable board games and pieces tucked into pockets. The skirts later fell into obscurity in the late 1950s.

These tight nylon pants had zippers and pockets covering the legs. They cost $25-$30 per pair in the early 1980s. Panno D'or claimed to have invented them between 1982 and 1983. Female prison inmates sewed early pairs after corrections officers suggested the workforce. The fad peaked in 1984-1985 and lasted about two years, when they were discontinued before baggy styles took over.

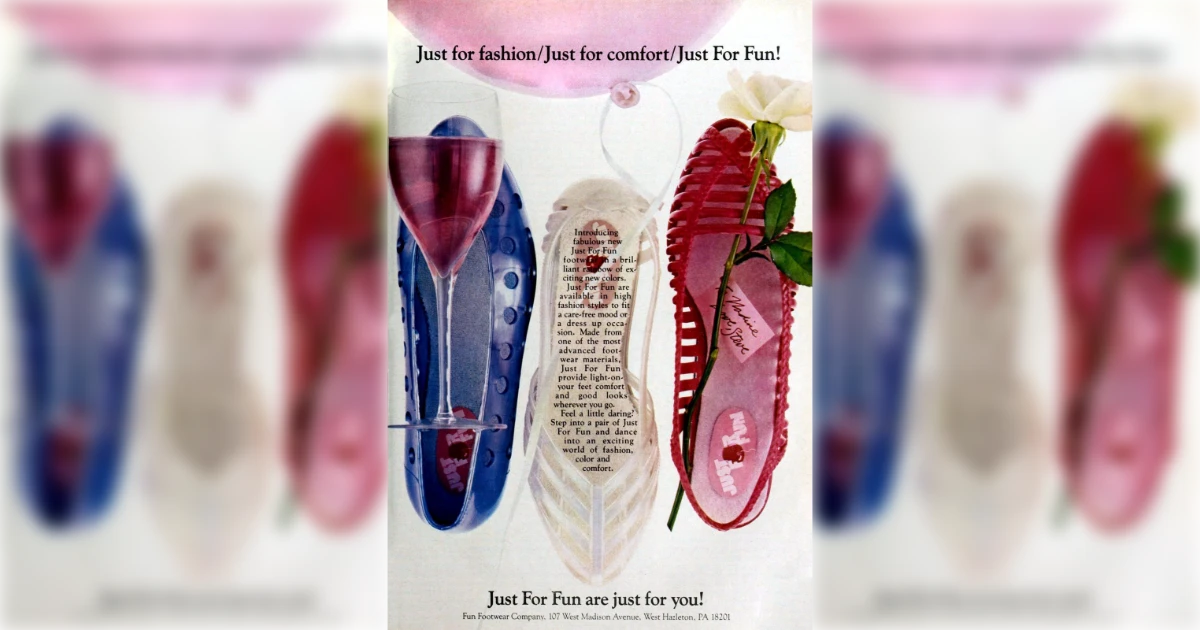

Tony Alano and Nicolas Guillon founded Jelly Shoes in Paris in 1980. They made PVC plastic shoes in 12 colors, each scented with vanilla or lemon. The founders dyed the first 200 pairs in their kitchen, dried them in their bathroom, and packaged them in their living room. A Bloomingdale's buyer ordered 2,400 pairs after seeing them at a shoe show. Americans first saw them at the 1982 Knoxville World's Fair. Some say artist Salvador Dalí's friendship with Tony Alano inspired the shoes.

Two Minnesota bodybuilders designed Zubaz in 1988 for athletes who needed comfortable workout wear. The baggy pants had elastic waistbands and wild zebra stripes in bright colors. Professional wrestlers Road Warrior Hawk and Road Warrior Animal owned half the company and wore the pants on NWA wrestling shows. The company sold $100 million worth of products in 1991 alone. Female prison inmates handled early production. In a 1993 Inside Sports survey, Zubaz finished third for "Worst Thing to Happen in Sports," behind Michael Jordan's retirement and wrestler Dino Bravo's death.

Generra released these heat-sensitive shirts in February 1991. The fabric changed color with temperature. Matsui Shikiso Chemical of Japan supplied the thermochromic pigment. The company sold $50 million worth between February and May 1991. The color change used crystal violet lactone dye, benzotriazole, and quaternary ammonium salt. Hot water, bleach, or tumble drying killed the effect. After a few washes, the shirts froze into a purple-brown color. They also showed sweat stains, revealing gross puddles under the armpits. Generra went bankrupt in 1992.

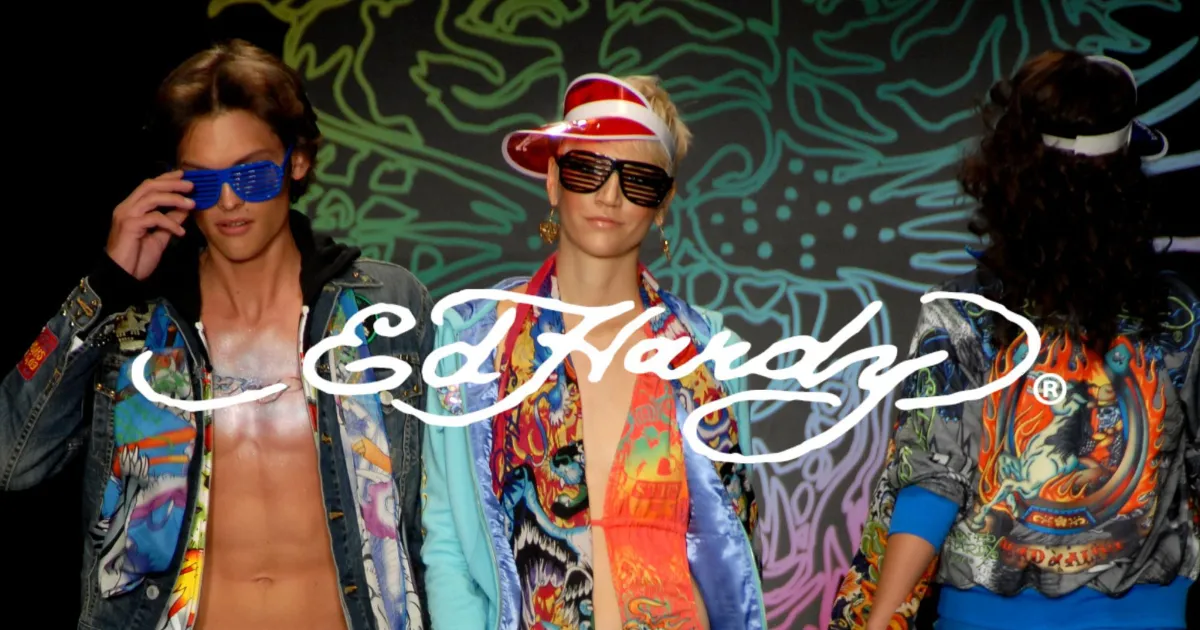

Christian Audigier licensed Don Ed Hardy's tattoo artwork between 2003 and 2005 to create a clothing line. The brand peaked at more than $700 million in 2009 but collapsed in two years. Don Ed Hardy blamed Audigier's marketing choices, including putting his own name on one item 14 times compared to Hardy's name once. The brand's link to reality TV celebrity Jon Gosselin and the Jersey Shore cast sped its downfall. In 2010, a New Orleans nightclub banned Ed Hardy clothing with a sign: "If it's on the Jersey Shore, it's not coming through the door."

Jessica McClintock invested $5,000 to partner with the founders in 1969. They made prairie, Victorian, and Renaissance-inspired dresses. The name came from the burlap trim (gunny sack) in earlier designs. They only made items with the original black label in 1969. Those remain the most valuable. Hillary Clinton wore a Gunne Sax dress when she married Bill in 1975. The brand shifted to prom dresses in the 1980s, with tighter, full-skirted designs in taffeta or satin.

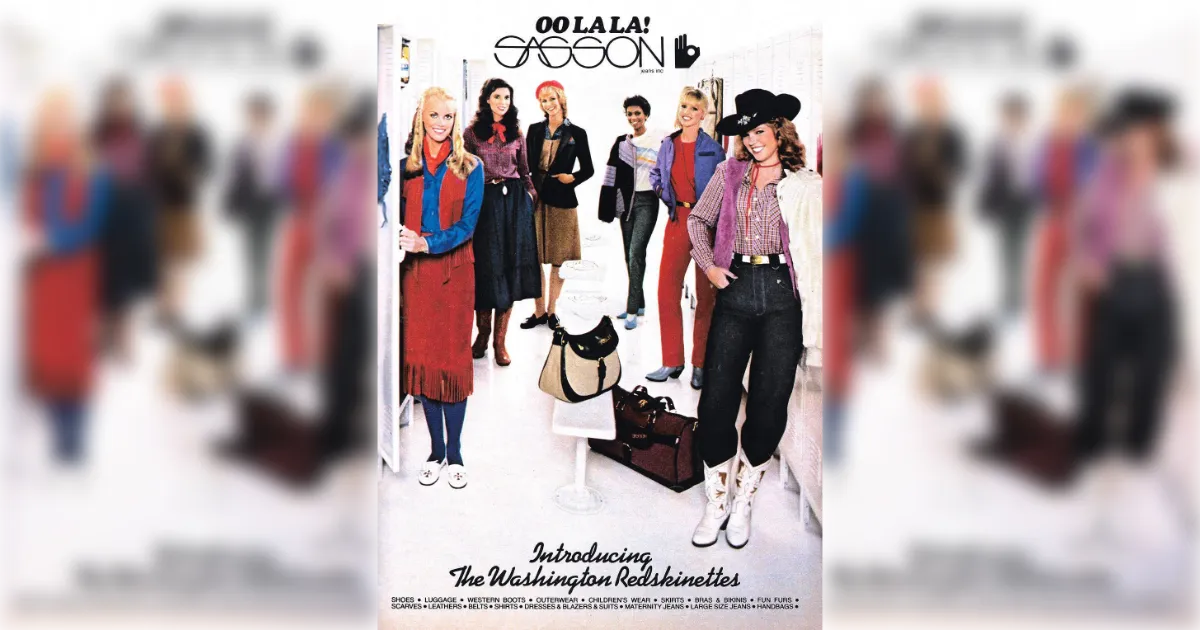

Sasson jeans rode the premium denim wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s when designer jeans became status symbols. The French-cut jeans had embroidered designs that made them must-have items. Cheap imports hurt the brand as tastes shifted. People stopped wanting elaborate embroidered designs. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1986.

Bugle Boy became the face of parachute pants in the 1980s. The nylon pants had zippers and cargo pockets. The ad campaign "Excuse me, are those Bugle Boy jeans that you're wearing?" made the brand famous. The clothes sold well to men and boys, but not to women. The company also made regular jeans and cargo pants, but became tied to the parachute pants fad. Bugle Boy filed for bankruptcy in 2001. Buyers tried to revive it but failed.