.webp)

General Foods

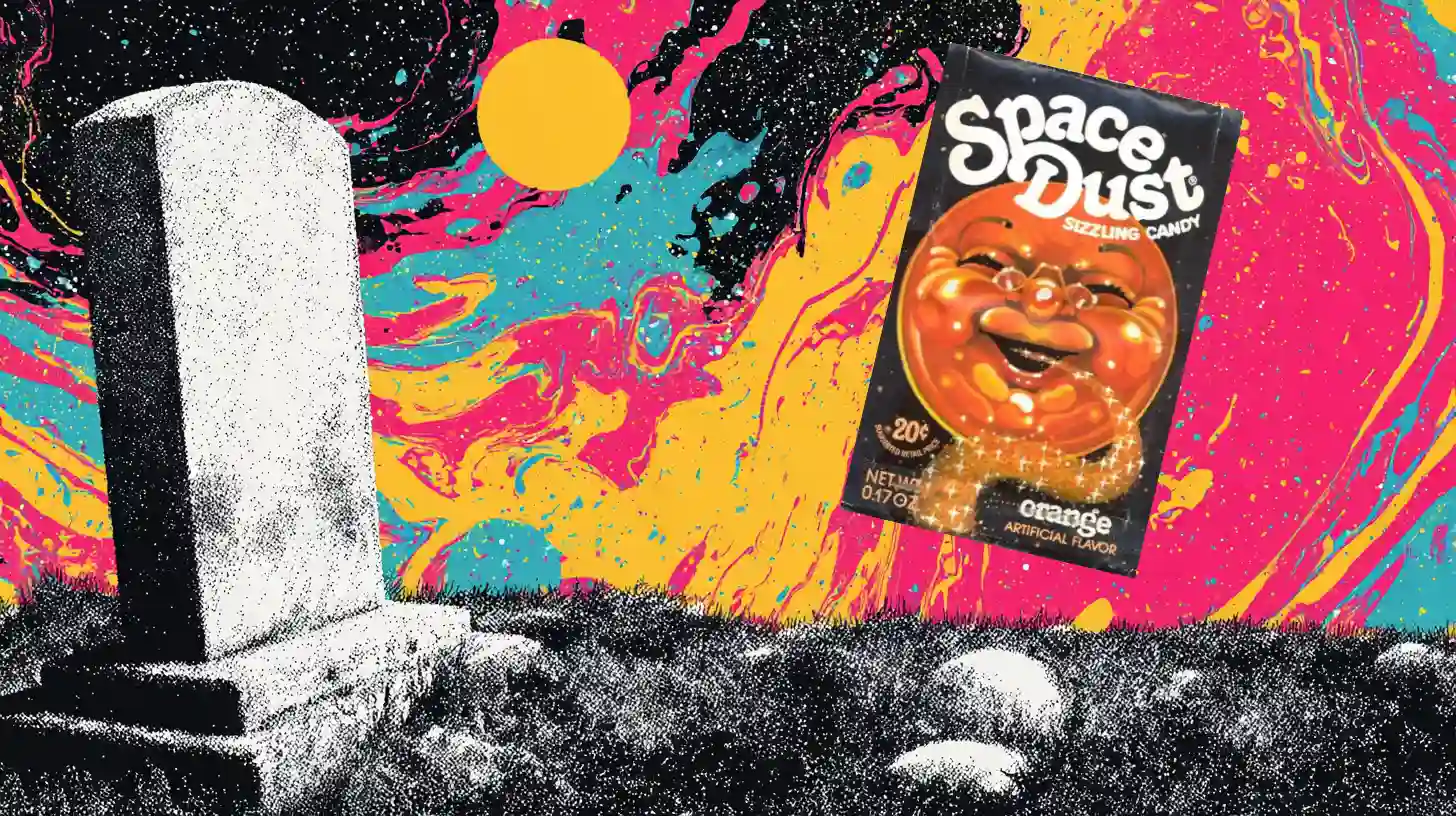

One of the most iconic candies happened by accident. Such was the case with Space Dust, a candy that literally exploded in your mouth—and eventually exploded in the marketplace for all the wrong reasons.

It's 1956, and William A. Mitchell is hunched over his laboratory bench at General Foods Corporation, trying to solve what seemed like a simple problem. He was tasked with creating an instant soda mix—just add water and voilà, fizzy drink. But like many discoveries, they sometimes come from spectacular failures.

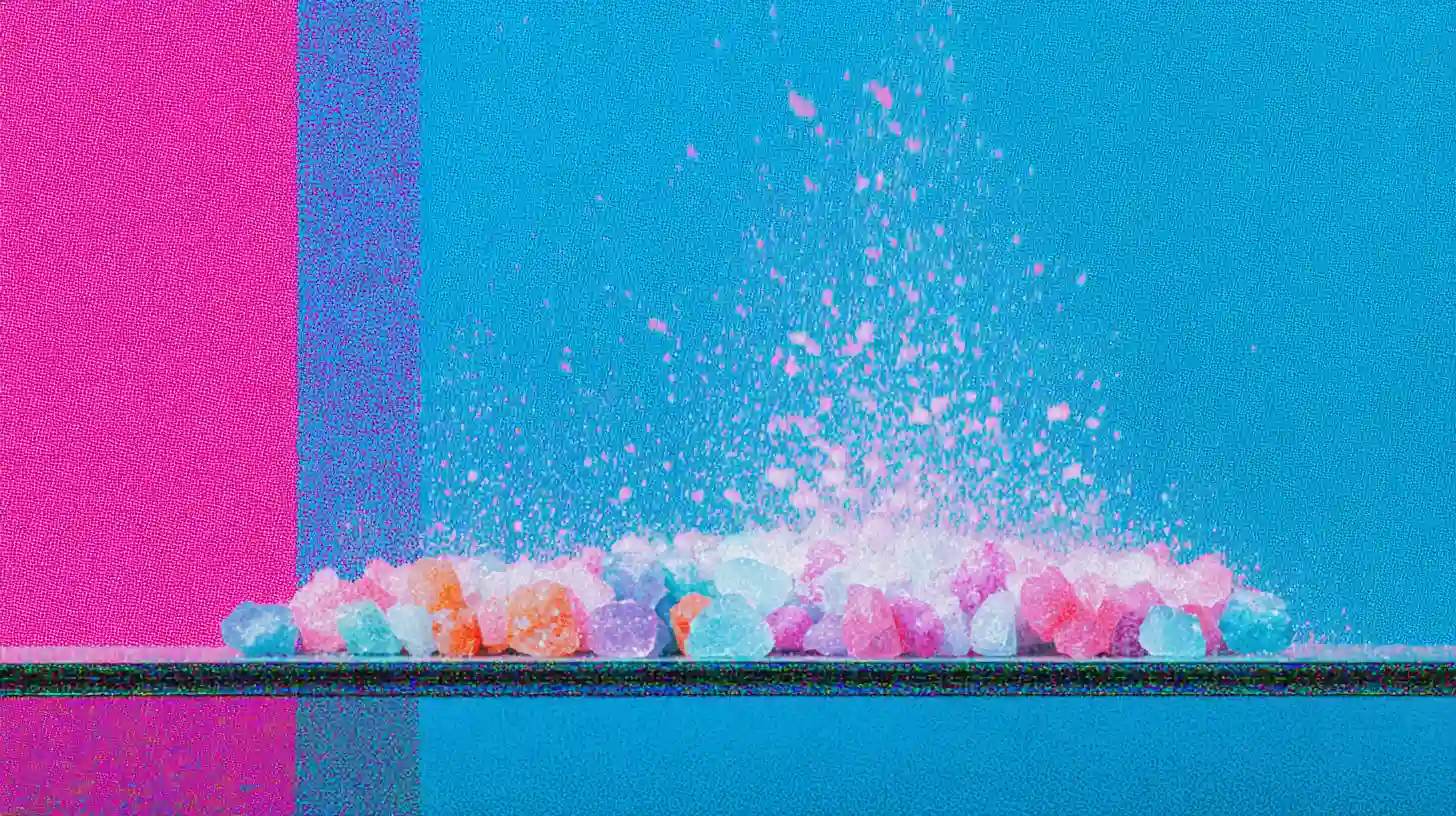

Mitchell was attempting to trap carbon dioxide in candy tablets when something magical happened. Instead of creating a powdered drink mix, he produced crystalline chunks that popped and crackled when they hit your tongue. Curious about his creation, he added some pineapple flavoring and convinced his secretary to be his first taste tester.

They were convinced they were on to something extraordinary.

But here's where the story gets frustrating. Mitchell received his patent in 1961, calling his invention "Gasified Confection" (inventors are sometimes not the best branders). General Foods executives weren't exactly thrilled about diving into the candy business. They were cereal and dry food people. This weird popping candy seemed too much like a science experiment.

For nearly fifteen years, Mitchell's invention sat on a shelf, gathering dust.

Everything changed in the early 1970s when Herman Neff, General Foods' new Vice President, tried the decades-old experimental candy. He was amazed. Finally, in 1975, the company launched the candy under the name Pop Rocks.

The success was immediate and explosive—literally. Executives described sales as "gangbusters," with hundreds of millions of dollars flowing in during those first few years. Kids everywhere were experiencing candy that popped in their mouths for the first time.

In 1976, Pop Rocks reached peak cultural relevance when Johnny Carson tried them live on "The Tonight Show."

By 1978, General Foods decided to expand their popping candy empire. So they reformulated Pop Rocks into powdered form.

They called it Space Dust.

The marketing was brilliant. While Pop Rocks focused on the popping sensation, Space Dust emphasized taste with "out of this world" flavors: Galactic Grape, Cosmic Cherry, and Orbiting Orange. The packaging was inspired by 1970s psychedelia—swirling planets and cosmic imagery that looked like it belonged on a prog rock album cover.

Initially, Space Dust was even more successful than Pop Rocks. Stores couldn't keep it in stock. Street vendors were hawking packets at marked-up prices like they were selling concert tickets.

But then came the phone calls. Angry parents were flooding General Foods with complaints, and their concern wasn't about sugar content or artificial flavoring. It was about the name itself.

"Space Dust" looked and sounded too much like "Angel Dust"—the street name for PCP, a dangerous hallucinogenic drug. Parents were horrified that their children were walking into stores asking for something that sounded like an illegal substance. Some even accused the company of deliberately trying to normalize drug culture among kids.

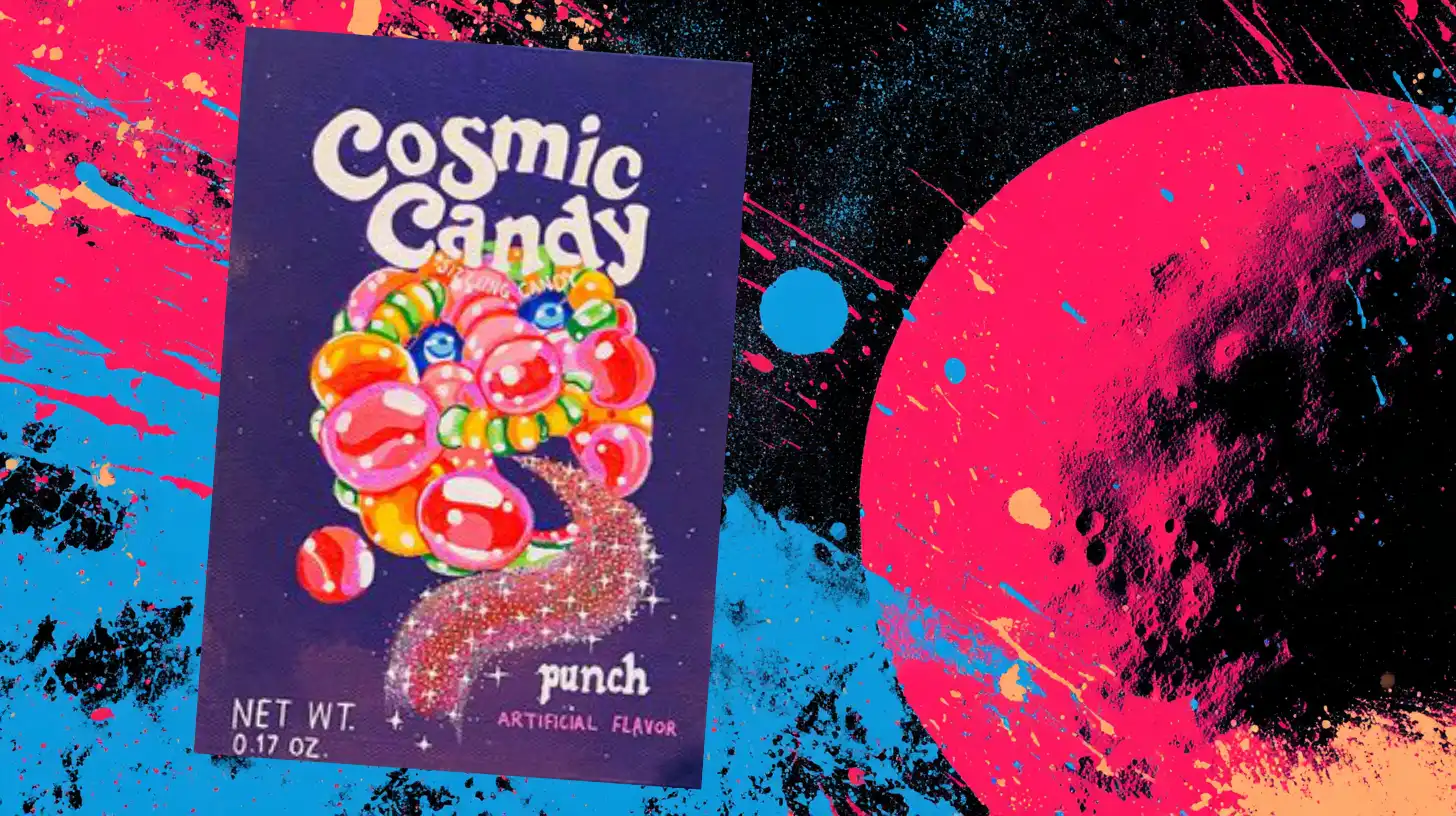

General Foods didn't fight back. They couldn't afford to. So they rebranded Space Dust to "Cosmic Candy." Same product, same space-themed packaging, different name.

Just when things seemed to stabilize, a new problem emerged—one that would ultimately doom both Space Dust and Pop Rocks. Rumors started to spread that if you ate Pop Rocks (or Cosmic Candy) and drank soda, your stomach would explode!

The myth became widespread. Kids whispered that Mikey, the adorable child from the Life cereal commercials ("He likes it! Hey Mikey!"), had died this way. Of course, it wasn't true—Mikey was alive and well.

By 1979, General Foods was in full crisis mode. They sent Mitchell himself on a publicity tour, explaining that the candy contained less carbon dioxide than half a can of soda. They took out full-page newspaper ads featuring Mitchell surrounded by children. They even provided his mailing address, inviting concerned parents to write directly.

The FDA stepped in, setting up a hotline in Seattle to assure parents that popping candy wouldn't cause children to choke or explode.

Despite every effort, the damage was irreversible. Sales plummeted as parents steered clear of the "dangerous" candy. By 1982, Space Dust—now Cosmic Candy—was discontinued. Pop Rocks followed in 1983, though it would eventually make a comeback.

Space Dust, however, never returned.