© History Oasis

This is a short history of 1960s fashion when the miniskirt met the space age.

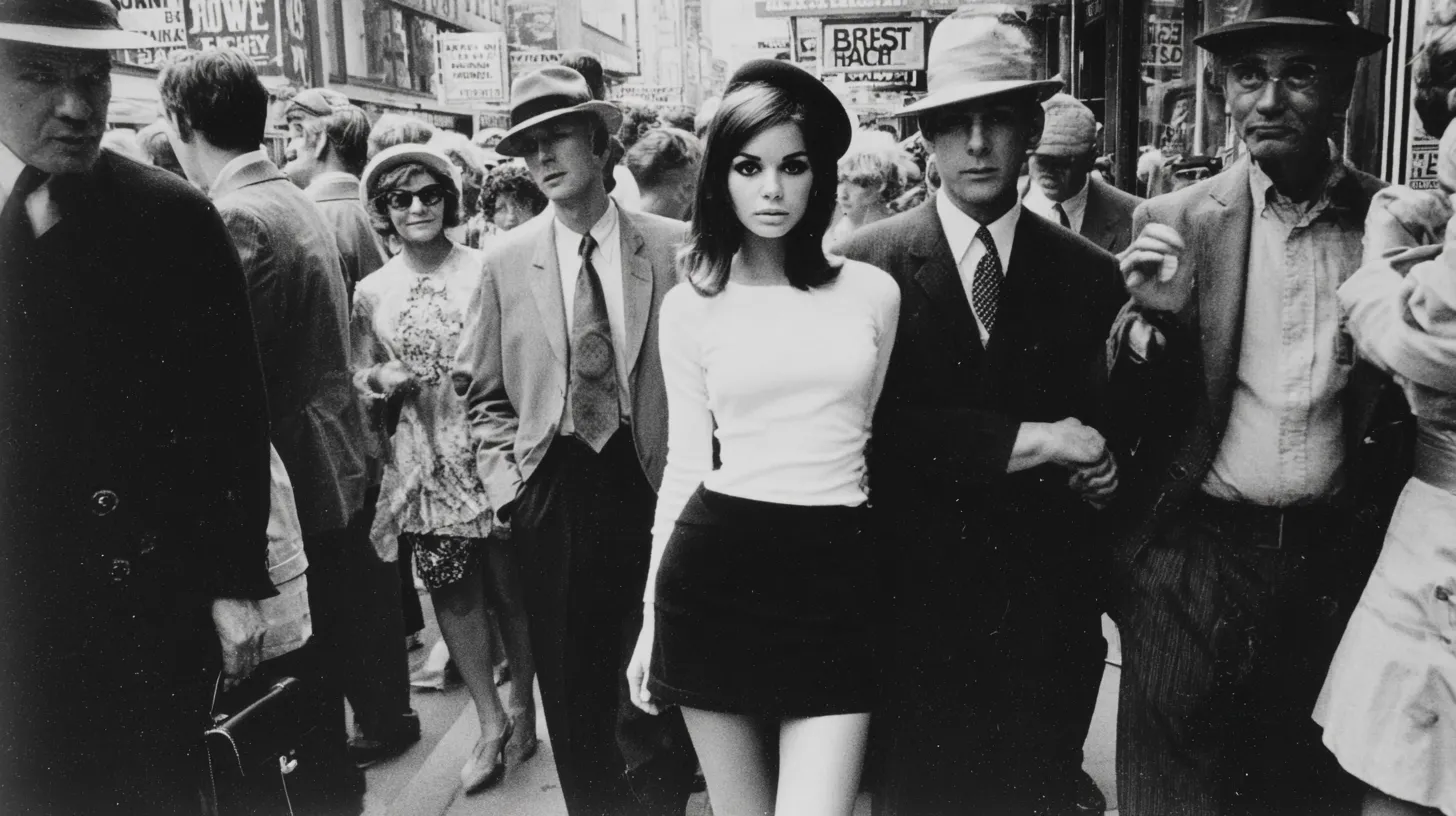

Imagine you are at a busy New York street grinding to a halt as crowds gather to stare at... a hemline. In 1965, British models showcasing miniskirts literally stopped traffic. Mary Quant’s rule? Four inches below the butt, max. When Jean Shrimpton wore one to Australia’s Melbourne Cup with no stockings or gloves, it sparked international scandal.

What started as a marketing gimmick to sell paper napkins almost revolutionized the entire fashion industry. Scott Paper Company created simple A-line shift dresses for $1 in 1966, expecting modest sales. Instead? Half a million orders flooded in within a year. Industry experts predicted 75% of Americans would be wearing disposable paper outfits by 1971, creating a $200 million market. Companies like Mars of Asheville pumped out 80,000 paper garments weekly. Even Campbell’s Soup joined the craze with their “Souper Dress” featuring Andy Warhol’s iconic design.

Frank Sinatra’s daughter sang and breathed boots. When “These Boots Are Made For Walking” hit #1 in 1966, Nancy toured with a mind-boggling collection of 250 pairs of go-go boots. The cultural impact was massive: TV shows like Hullabaloo made white boots mandatory for female dancers, earning them the nickname “hullabaloo boots.”

The space race wasn’t just happening in NASA labs, it was also unfolding on the runway. André Courrèges dropped his “Moon Girl” collection in 1964, complete with white go-go boots and spherical helmets that screamed “future human.” NASA was so impressed by Pierre Cardin’s space-age designs that they actually invited him to Cape Canaveral.

Meanwhile, Paco Rabanne went full sci-fi with his “12 Unwearable Dresses” made from chain mail and aluminum. When he designed Jane Fonda’s Barbarella costumes, fashion and space fantasy merged completely.

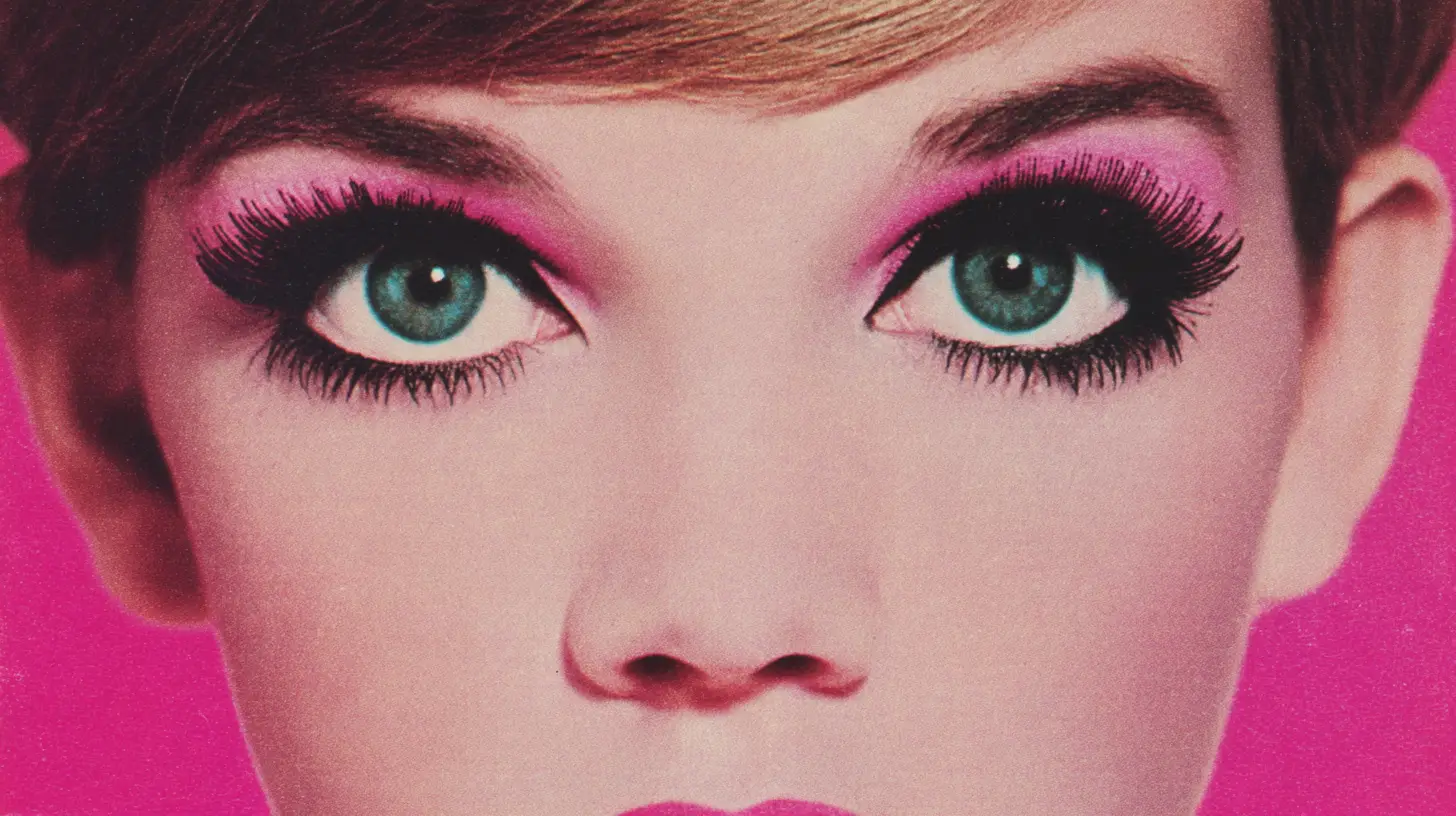

Twiggy’s iconic doll-like eyes weren’t natural. To achieve her signature look, she stacked three layers of false eyelashes on top, then painted squiggly stick-lashes beneath her eyes for extra drama. The trend exploded so massively that Yardley cosmetics created “Twiggy lashes” — three-tiered false eyelashes that became an overnight sensation. Department stores even redesigned their mannequins to mimic her look.

Gender roles? What gender roles? The 1960s completely flipped fashion’s script. Twiggy revealed she used to go to men’s tailors to have suits made because she loved that boyfriend-y look. But the revolution went both ways. Women started raiding men’s fashion playbooks, wearing straight-legged pant suits in traditionally masculine fabrics for everyday wear. Twiggy’s androgynous style deliberately blurred the lines between what boys and girls should wear.

Welcome to the future. Circa 1965. Designers like Mary Quant discovered PVC, previously only used for raincoats, and went absolutely wild with it. Picture models strutting down runways studded with protruding metal plugs, with neon lights radiating off white PVC. The look made their entire bodies appear like walking circuit boards. The 1960s fell head-over-heels for synthetic materials. PVC, polyester, acrylic, nylon, rayon, and Spandex were all on the rage.

Boutiques created a “frenetic atmosphere” where modern music played and young owners and customers collaborated on new looks that came only in small sizes. London’s Carnaby Street and Kings Road became the epicenter of boutique culture, with America opening Paraphernalia on Madison Avenue in New York in 1965 as an instant smash hit. This represented a shift from a designer-centric fashion ecosystem to one where the consumer was at the center of creation.

The “Dolly Girl” archetype emerged in the mid-1960s, characterized by the iconic miniskirt and childish-looking clothing that was “worn tight fitting, sometimes even purchased from a children’s section.” Dresses were often embellished with lace, ribbons, and other frills, topped off with light colored tights.

In 1968, fashion discovered “hardware” — accessories consisting of metal squares, nailheads, rattling chains, zippers, brass buttons, and clamps became the new trend. This industrial aesthetic was part of the decade’s fascination with futuristic, space-age materials and represented a complete departure from traditional feminine accessories.