.webp)

© History Oasis

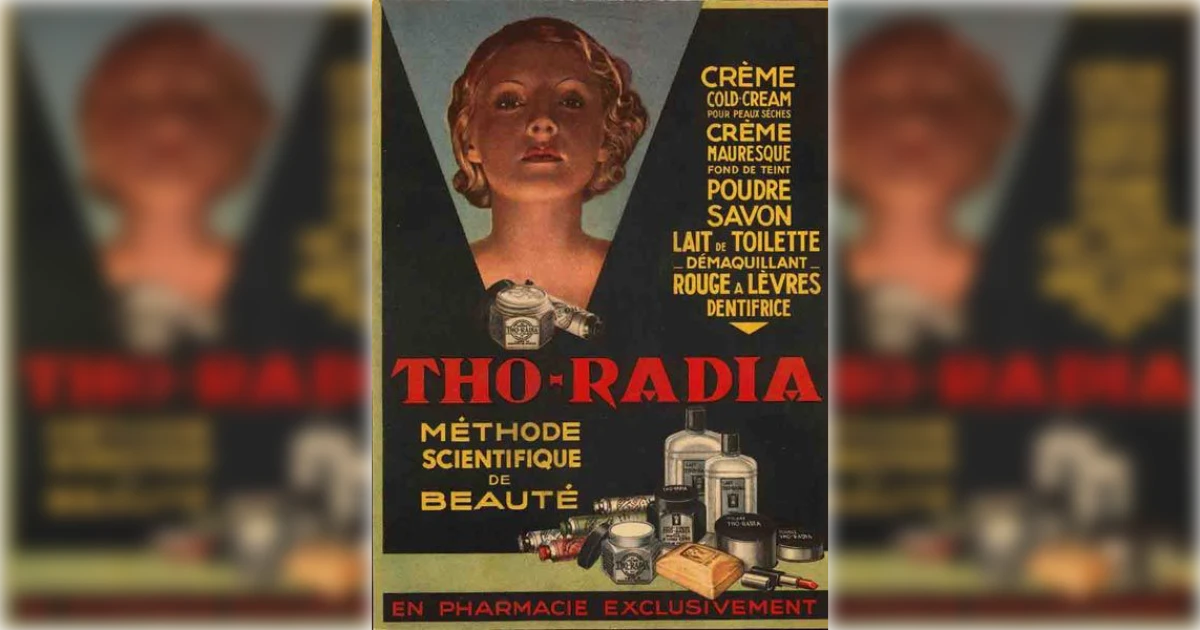

Discontinued: 1962 (radioactive ingredients removed in 1937)

It’s 1932 Paris, and women are glowing with beauty—thanks to actual radium in their face cream.

French pharmacist Alexis Moussalli partnered with Dr. Alfred Curie (cleverly named but no relation to the Curies) to create what they called “scientific beauty products.” Their entire line—face creams, powders, lipstick, even toothpaste—contained genuine radium bromide and thorium chloride.

They used Art Deco packaging featuring a luminous blonde woman bathed in otherworldly light. The tagline? “Le Radium au service de la beauté” (Radium at the service of beauty).

Women paid premium prices for radioactive skincare, believing the energy would give them that coveted healthy glow. The French government finally banned radioactive cosmetics in 1937, but the company kept the name and continued operating until 1962.

Discontinued: 1933

The 1930s beauty industry promised women they could “radiate personality” with permanently darkened lashes. Lash Lure delivered along with the side effects of blindness and death.

This coal-tar-based dye contained para-phenylenediamine (PPD), a chemical so toxic it caused horrific blisters, corneal ulceration, and sometimes fatal bacterial infections. The most documented victim, known in court records only as “Mrs. Brown,” experienced eye ulcers that oozed and swelled shut within hours of treatment.

More than a dozen women lost their sight. At least one died.

The tragedy sparked national outrage when the FDA displayed before-and-after photos at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair in their “Chamber of Horrors” exhibit. Eleanor Roosevelt herself visited the display, reportedly pressing the photographs to her chest and crying, “I cannot bear to look at them.”

This single product’s devastation directly led to the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

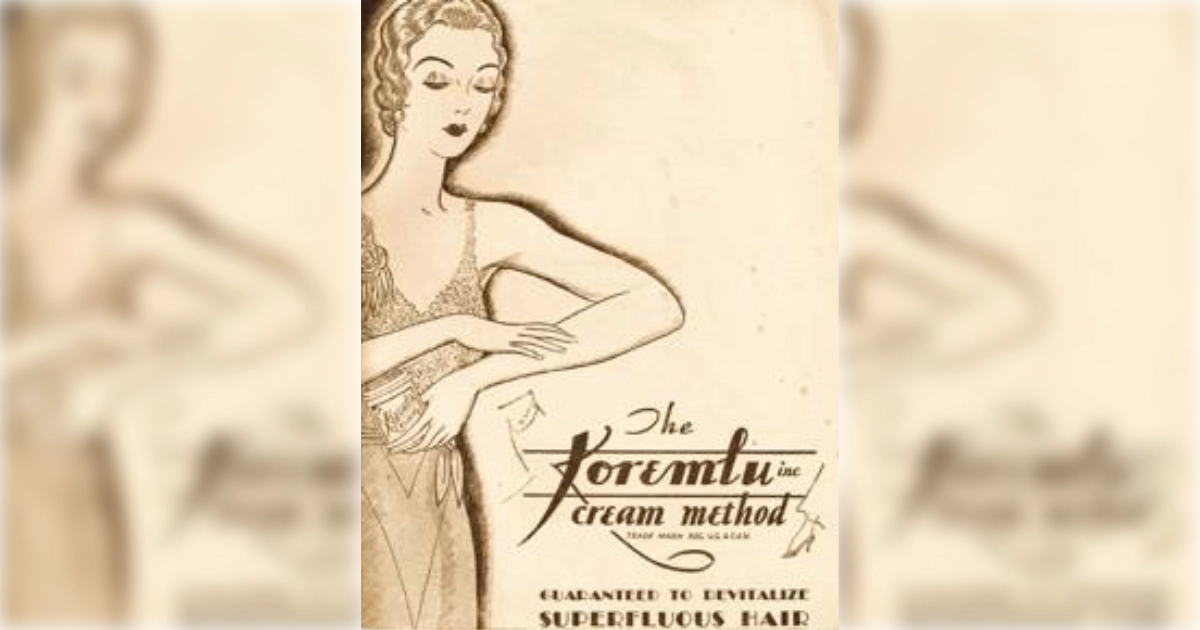

Discontinued: 1932

Kora M. Lubin created a permanent hair removal that was “safe and effective.” Her cream, cleverly named after herself (KOra luBIN = Koremlu), promised to eliminate unwanted hair forever.

There was just one tiny problem. The active ingredient was thallium acetate, better known as rat poison.

Within a year of its 1930 launch, over 120,000 jars flew off the shelves. Then the horror stories began pouring in. Paralysis, blindness, respiratory failure, and death. One 26-year-old woman lost her teeth, eyesight, ability to walk, and her job after using Koremlu.

Hospitals across the country treated patients experiencing thallium poisoning symptoms, excruciating abdominal pain, the sensation of “walking on hot coals,” and complete hair loss.

By July 1932, the company filed for bankruptcy, facing $2.5 million in damage suits.

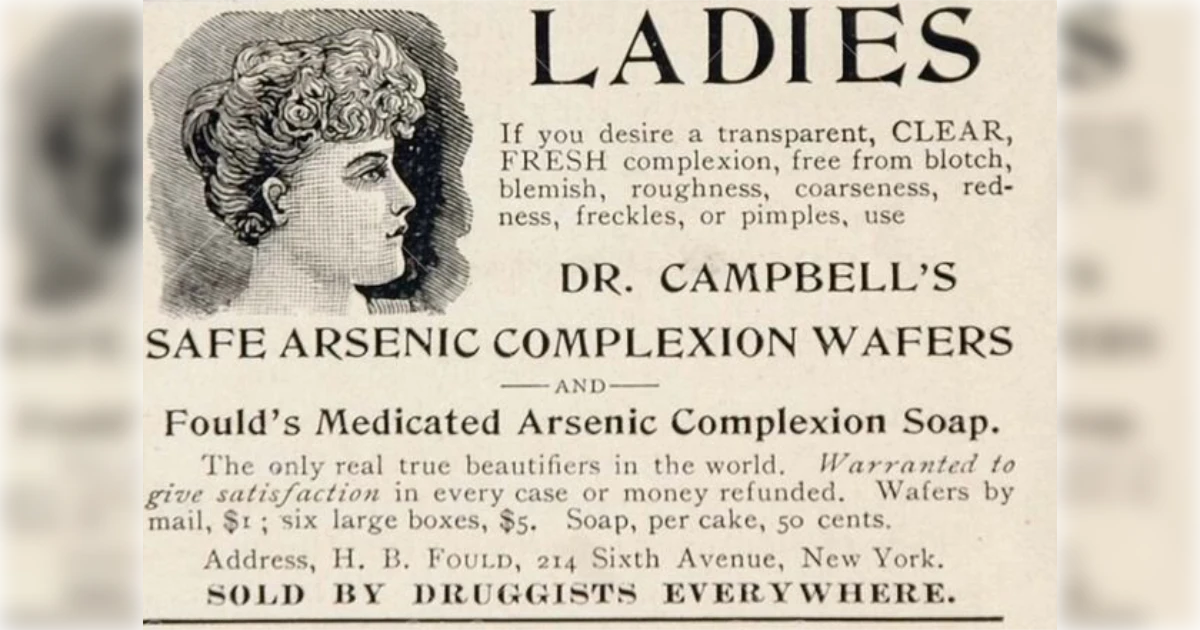

Discontinued: Early 1900s

Victorian women had the odd goal of looking like they were dying of tuberculosis. The translucent, deathly pale skin of consumption victims was considered the height of fashion.

So Dr. James P. Campbell came up with an “absolutely harmless” solution. Edible arsenic wafers were available through the Sears & Roebuck catalog and local drugstores.

These innocent-looking white wafers promised to deliver “a deliciously clear complexion” free from freckles, blackheads, and “vulgar redness.” Women were instructed to delicately nibble them like after-dinner mints, slowly poisoning themselves for beauty.

The Victorian obsession with pale skin ran so deep that women knowingly consumed a known poison.

Of course, there’s no such thing as safe arsenic. Long-term exposure caused the exact skin problems women were trying to solve: dark spots, rashes, and hyperpigmentation. The irony? It made their competition far worse.

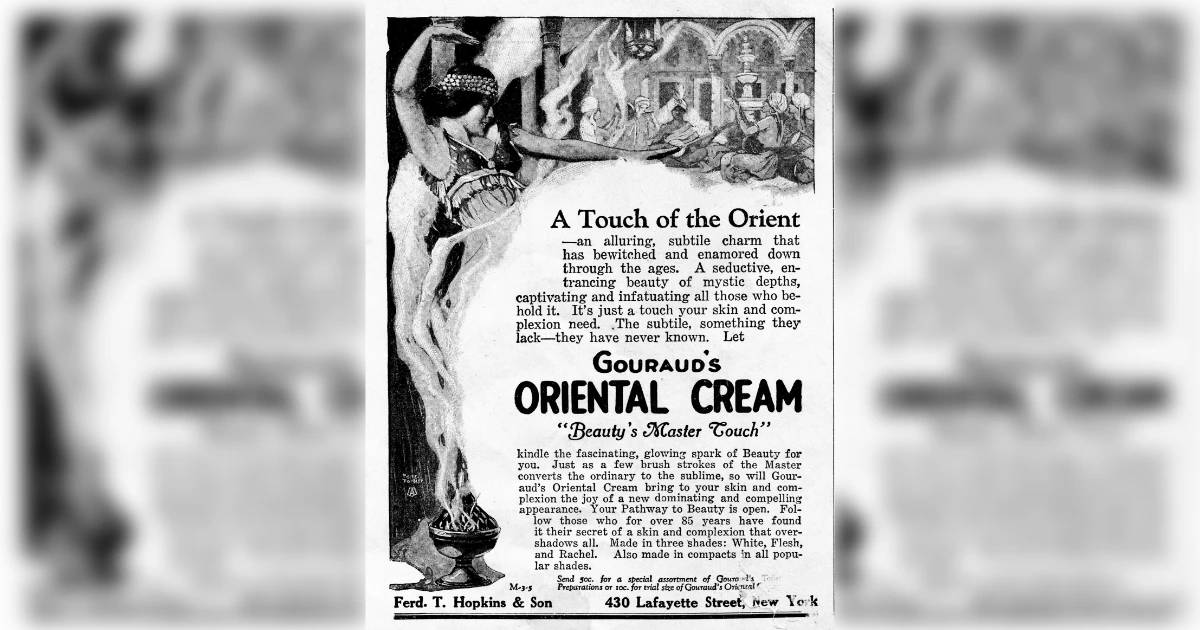

Discontinued: 1930s

For over 50 years, Dr. T. Felix Gouraud’s “Oriental Cream or Magical Beautifier” was the go-to solution for women seeking flawless skin. Advertisements promised it would remove “tan, pimples, freckles, moth patches, rash, and skin diseases.”

The secret ingredient? Mercury.

Specifically, calomel, a mercury compound that literally ate away at skin tissue while promising to beautify it. Women faithfully applied this “magic beautifier” daily, not knowing they were slowly poisoning themselves.

The symptoms of mercury poisoning are horrific. Dark rings around the eyes and neck, bluish-black gums, loose teeth, and eventually death. Yet Gouraud’s Oriental Cream remained popular for decades.

The product survived multiple generations of users, passed down from mothers to daughters like a toxic family heirloom, before the deadly cosmetic product was discontinued.

Discontinued: 1930s-1940s

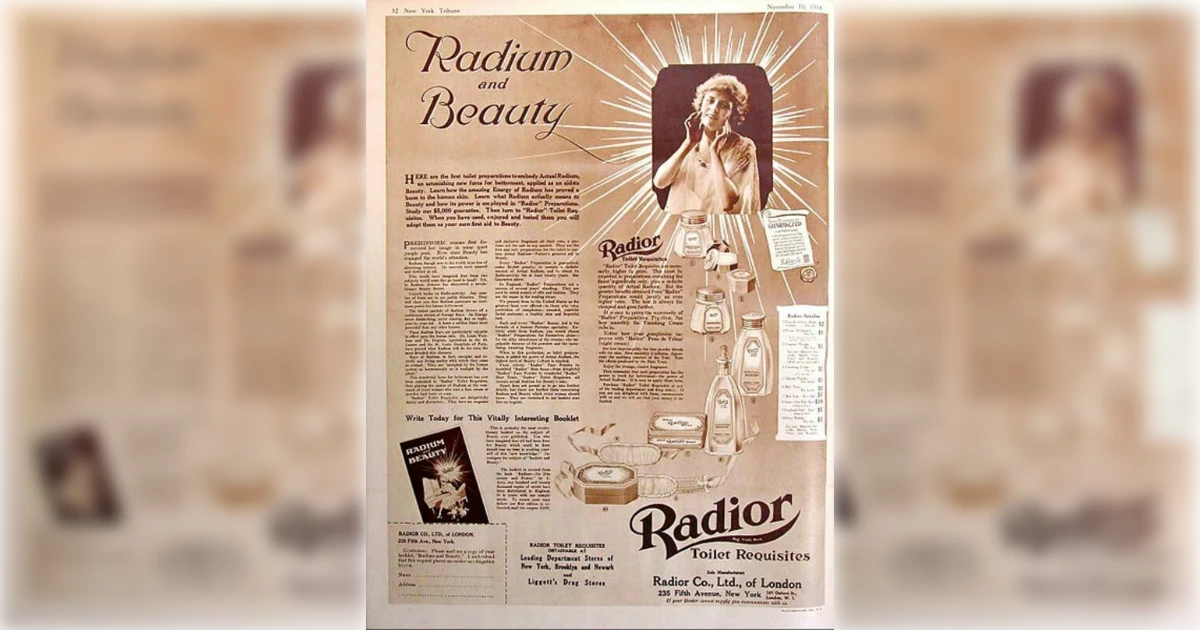

The 1920s and 30s were the golden age of “radium therapy.” This was a time when radioactive materials were considered the ultimate health and beauty treatment.

Upscale spas across America offered relaxing soaks in radioactive water, rejuvenating radium mud facials, and energy-boosting radium drinks. Women would travel hundreds of miles to bathe in naturally occurring radium springs, believing the “liquid sunshine” would give them that healthy glow from within.

Some establishments even offered radium-infused beauty products to take home, including face creams, bath salts, and drinking water.

The Radium Girls tragedy of the 1920s—where watch dial painters suffered severe radiation poisoning—began exposing the dangers, but the beauty industry was slow to adapt.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that the connection between radiation exposure and cancer became undeniable.

Discontinued: Early 1900s

Victorian women discovered that large, dilated pupils made them look more alluring. The problem? How to achieve this look safely.

Their solution was anything but safe: belladonna eye drops.

Belladonna, also known as “deadly nightshade,” literally translates to “beautiful lady” in Italian—a reference to this exact cosmetic use. Women would squeeze drops of this potent toxin directly into their eyes, dilating their pupils for hours.

The effect was undeniably striking. Those wide, dark pupils created an otherworldly, almost hypnotic gaze that fit perfectly with Victorian romantic ideals.

The side effects were less romantic. Blurred vision, light sensitivity, and frequent blindness. Many women became addicted to the drops, unable to achieve their desired look without them.

Some desperate women tried alternatives like citrus juice or perfume in their eyes, but belladonna lasted longer and was more effective. That was if you survived it.

.webp)

Discontinued: Gradually through the 1800s

For centuries, the ultimate status symbol was skin so pale it looked porcelain—achieved through lead-based face paints called ceruse.

Queen Elizabeth I was the most famous devotee, coating her face in thick white lead makeup that created her iconic ghostly appearance. The look was so associated with nobility that commoners couldn’t afford to achieve it.

Women would apply ceruse like armor, creating a mask-like appearance that required avoiding all facial expressions (the paint would crack if you smiled). The makeup was so heavy and toxic that users had to continuously reapply it to cover the skin damage it caused.

The lead slowly poisoned users, causing hair loss, tooth decay, and eventual death. Elizabeth I’s own health problems were likely exacerbated by decades of lead exposure, though she continued using it until her death.

Lead-based cosmetics gradually disappeared as understanding of lead poisoning improved.

Discontinued: 1930s-1940s

Red lips and rosy cheeks were essential to Victorian beauty, achieved through mercury sulfide. This was a compound so toxic it’s now used as a hazardous waste warning.

Vermillion, the most prized red pigment, was pure mercury sulfide. Women applied it directly to their lips and cheeks, not knowing they were absorbing deadly toxins through their skin.

Beauty manuals of the era even recommended mercury-based ointments for eyelash growth, instructing women to rub the poison directly onto their eyelids.

The 1874 “Ugly Girl Papers” in Harper’s Bazaar suggested “ointment of nitric oxide of mercury mixed with lard” for fuller lashes.

Mercury poisoning symptoms developed slowly. Tremors, mood swings, memory loss, and eventual organ failure. Many women attributed these effects to hysteria or feminine weakness rather than their daily beauty routine.

The vibrant colors achieved through mercury were unmatched by safer alternatives, keeping the products popular even as medical knowledge advanced.

Discontinued: 1940s

The 1920s promised women permanent hair removal through the miracle of X-ray technology.

Upscale salons offered this “scientific” treatment, positioning patients under primitive X-ray machines that bombarded unwanted hair follicles with radiation. It did work. Hair was permanently destroyed, never to return.

The marketing positioned the treatment as modern, painless, and permanent. No more tedious shaving or painful wax treatments. Just a few sessions under the X-ray machine and you’d be hair-free forever.

What they didn’t advertise were radiation burns, skin cancer, and cellular damage that wouldn’t manifest for years or even decades. Many women who received these treatments developed cancers later in life, often unaware of the connection to their beauty treatments.

The practice continued well into the 1940s, even as evidence of radiation dangers mounted.