© History Oasis

Between 1901 and 1910, clothing production changed everything. Factories started making ready-to-wear pieces while tailors still crafted custom garments. The middle class wanted style, and manufacturers delivered. But Edwardian fashion never lost its luxurious edge—silk, lace, velvet, and hand-sewn beading still ruled the best wardrobes.

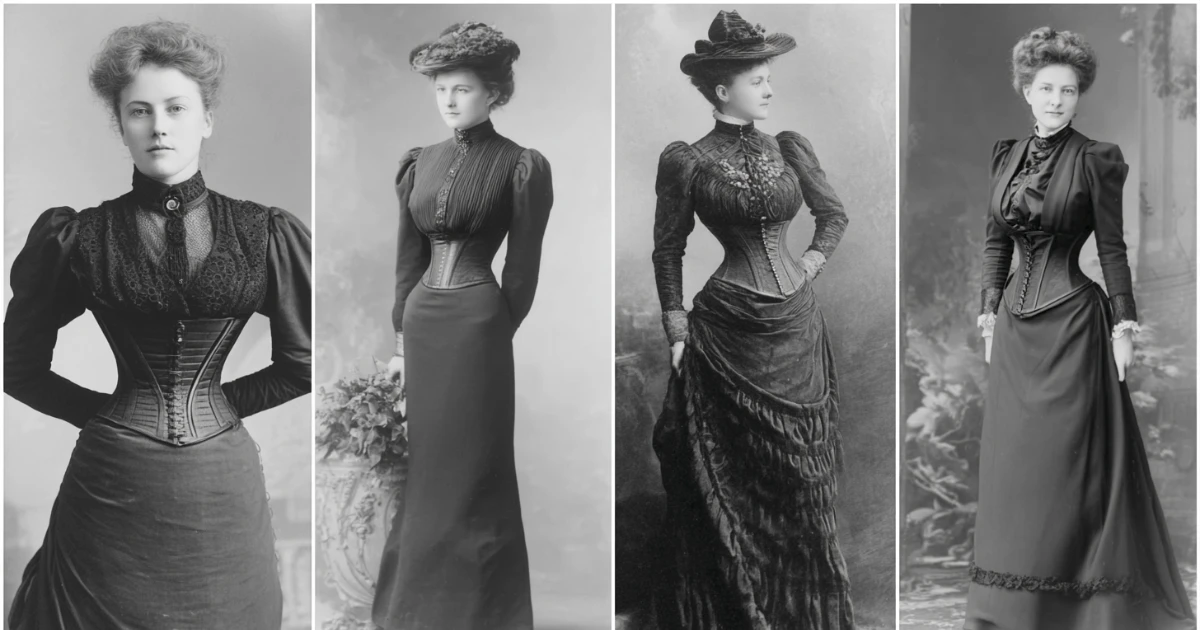

Women squeezed into brutal corsets to create that famous S-shape—chest pushed forward, hips thrust back. It looked dramatic but felt miserable. Then Paul Poiret showed up from Paris with a radical idea: loose, flowing dresses. His designs ditched the torture devices and let women breathe. Fashion would never be the same.

High, stiff collars dominated women's clothing, often trimmed with lace or embroidery. Sleeves hugged arms from shoulder to wrist. This wasn't just style—it was virtue signaling. The higher your collar, the more respectable you appeared. These details forced people to focus on faces and posture rather than bodies.

Skirts swept the floor and then some. Many featured trains that trailed behind like wedding dresses. Ruffles, lace, and intricate stitching covered every inch. The more elaborate your skirt, the clearer your message: you didn't need to work, walk fast, or worry about dirt.

Artist Charles Dana Gibson created the era's beauty standard through his pen-and-ink drawings. His Gibson Girl had massive, puffy hair piled impossibly high and secured with fancy combs. Real women spent hours recreating this look. It replaced the severe Victorian styles with something softer, more romantic—but just as time-consuming.

As women joined sports clubs and entered offices, fashion had to adapt. Tailored suits—matching skirts with fitted jackets or crisp blouses—became the uniform of the modern woman. These pieces moved with the body instead of against it. You could play tennis, ride bicycles, or walk briskly without your clothes sabotaging you.

Hats grew enormous, decorated with entire bird wings, silk flowers, and yards of ribbon. A proper lady never left home without gloves and often carried a parasol. These weren't just practical items—they were social armor. The right accessories marked you as refined, wealthy, and worth knowing.

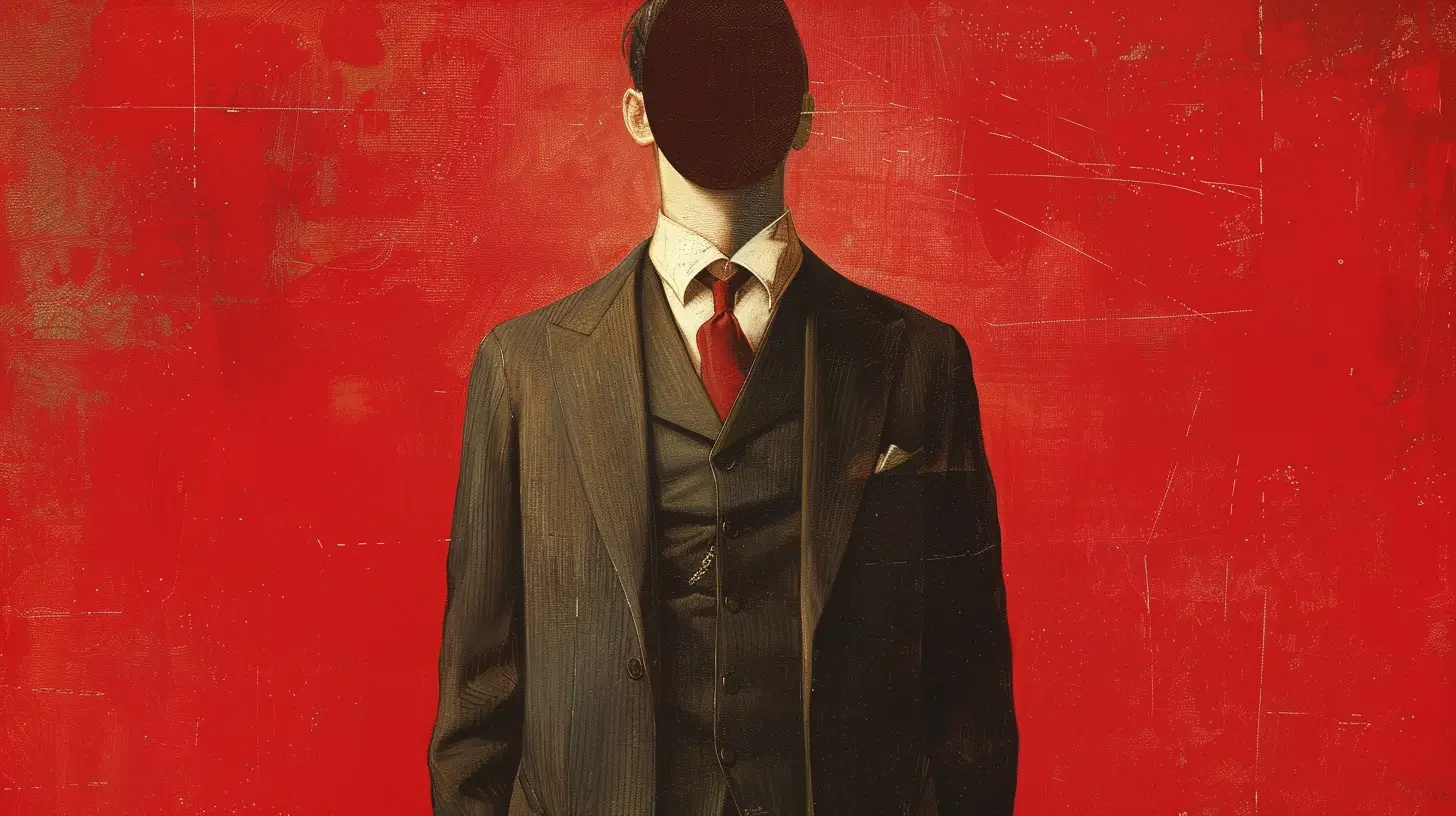

Men faced their own fashion constraints. Stiff, high collars cut into necks. Narrow trousers restricted movement. Frock coats and morning coats were required for any serious occasion. But change crept in—the loose sack coat offered relief for daily wear, and the new tuxedo jacket provided a less formal evening option.

Rich people with time to kill created a new market. They wanted clothes for tennis, golf, cycling, and lounging. This "leisure class" demanded lighter fabrics and looser cuts. Their influence trickled down, making casual clothing acceptable for everyone. Comfort started competing with formality.

Vogue and Harper's Bazaar became fashion bibles. These magazines brought Paris and London styles to small-town America. Middle-class women studied every illustration and photograph, desperate to copy high society. Fashion trends that once took years to spread now moved in months. The modern fashion cycle was born.